Beyond human imitation: Rethinking safety and purpose in robotics

Humanoid robots fascinate, but are they safe and practical? Discover why purpose-built designs outperform humanoid robots in reliability, stability, and compliance for real-world robotics.

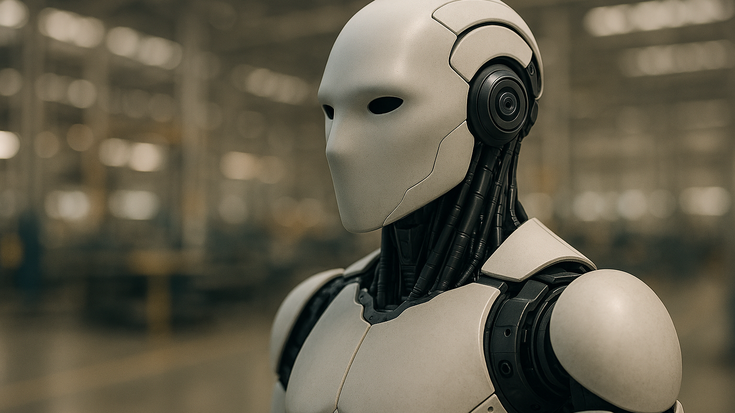

Humanoid robots have captured global attention, driven by visions of replacing human labor with machines that mirror human flexibility. While the concept is compelling, the human form factor introduces unique engineering challenges, particularly in stability, reliability, and safety.

The fascination with humanoid robots began in fiction and has evolved into significant real-world investment. Companies promise robots that look and act like humans, capable of performing diverse tasks. But does the human form truly represent the optimal design for robotics? To answer this, we must understand its evolutionary origins and engineering implications.

Evolutionary origins

The human body is the product of evolution and is shaped by survival needs. Its design reflects key features that enabled our ancestors to thrive. Forward-facing eyes provide depth perception, signaling a predator role; a high center of gravity supports energy-efficient locomotion over long distances; and dexterous hands are optimized for manipulation and tool use.

Together, these traits were fine-tuned for a nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

Drawbacks of the human form

While impressive, the human form introduces some limitations:

- Poor stability and agility compared to quadrupeds. Try to catch an uncooperative dog, and you know what I’m talking about.

- Unsuitability for repetitive tasks, leading to wear and injury over time, even with the impressive skills of regeneration and self-healing our bodies are not suited for 9 to 5 work on the assembly line with no job rotation. Our complex hands with many small joints are especially prone to injury and wear.

- Complexity and reliability issues: A humanoid robot with ~200 degrees of freedom (DoF) cannot match the uptime of a 6-DoF industrial arm because humanoids' extreme mechanical complexity means that even highly reliable individual components cannot prevent a collective drop in operational reliability.

- Reach and shape constraints: Compared to purpose-built machines, humans and humanoid robots are limited by their size and form. For example they are not designed to accommodate different grippers or to be adapted to accommodate specific applications.

Safety considerations

ISO 13849-1 is a key standard for the functional safety of machinery. One of its core concepts is the Performance Level (PL), which measures the probability that a safety-related function will fail. PL is expressed on a scale from PL=a (lowest) to PL=e (highest). In essence, the PL defines the risk of a dangerous failure per hour of machine operation.

For humanoid robots, stability is a critical safety concern. Walking robots depend on dynamic stability, meaning any interruption in power or a joint malfunction during movement can lead to a fall — a significant safety hazard.

Using ISO 13849-1 together with ISO/TR 14121-2 risk assessment methodologies, we can determine the required PL for a function that prevents robot falls. The assessment considers three factors:

Severity: A 30+ kg robot falling can cause injury. In controlled environments (protective footwear, no children, no stairs), severity may be low. In other cases, it must be considered high.

Frequency: High, due to close human-robot interaction.

Avoidance: Often impossible. For example, if a robot falls behind you, avoiding impact is unlikely.

Based on this analysis:

- In controlled environments with low injury severity, a minimum of PL=c is necessary.

- In complex environments with high potential severity, PL=e is required.

Achieving PL=e requires redundancy, robust design, high-quality components, and meticulous attention to safety and reliability throughout development and manufacturing. Even reaching PL=c is far from trivial.

Industry reality

Current humanoid industry practices raise alarms. Few humanoid robots, if any, provide credible stability and reliability claims, and the internet is full of videos of humanoids falling in spectacular fashion. There have been recent cases which raise serious questions about how highly the companies’ developing humanoids prioritize safety.

One of the most intriguing aspects of humanoid robotics is the regulatory and compliance landscape. In the world of industrial manipulators, including modern lightweight user-friendly robots (cobots), there is a well-established framework of safety standards. Most notably, ISO 10218-1 and ISO/TS 15066 define requirements for robot arms and provide guidance on acceptable force and pressure limits for impacts involving industrial robots.

However, these standards are rarely applied to humanoid robots and would only cover part of the humanoid robot application as ISO 10218-1 does not cover risks related to mobility of the robot. Existing standards are still immature and remain work in progress, for example ISO/WD 25785-1, which relates to the risks posed by loss of stability in dynamically stable industrial robots, which includes humanoids when used in industrial applications. For applications outside traditional industrial settings, regulation is even more limited.

This raises a critical question: what level of safety should we demand for humanoid robots operating in close proximity to people in public spaces? Today, the promise of humanoid robots appears to be based on an acceptance of a significantly lower level of safety compared to what is required for a robot manipulator in a factory, which often operates behind a safety fence. Are we truly prepared to embrace this risk? Like our approach to self-driving cars, it's important to have an open public dialogue about humanoids and safety.

Conclusion

The key question is whether we continue pursuing humanoid robots, a path that, in my view, risks creating systems that are complex, unreliable, and potentially unsafe. Alternatively, we can stay on the proven course of designing robots and home automation solutions where the form factor is purpose-built for the task. This approach delivers dedicated, cost-effective, safe, and reliable solutions.

Examples of this strategy are all around us: vacuum cleaners, washing machines, dishwashers in the home, and autonomous mobile robots (AMRs), industrial manipulators, SCARA robots, and delta robots in industry. These solutions demonstrate that specialization, rather than imitation of human form, leads to robust, safe and scalable automation.

Not for republication

- Universal Robots USA, Inc

- 27175 Haggerty Road, Suite 160

- 48377 Novi, MI